Interaction between the welfare state and the family: a historical analysis to face the future

Population ageing is undoubtedly one of the major challenges facing advanced societies in the near future. The drastic fall in the birth rate in recent decades, together with the notable and continuous increase in life expectancy in the last two centuries, make up a demographic transition that leads, inexorably, to a significant change in the composition of the population by age: the weight of the older generations will be increasingly greater. While increasing longevity is a major social achievement, its possible effects on living standards and well-being are a major concern.

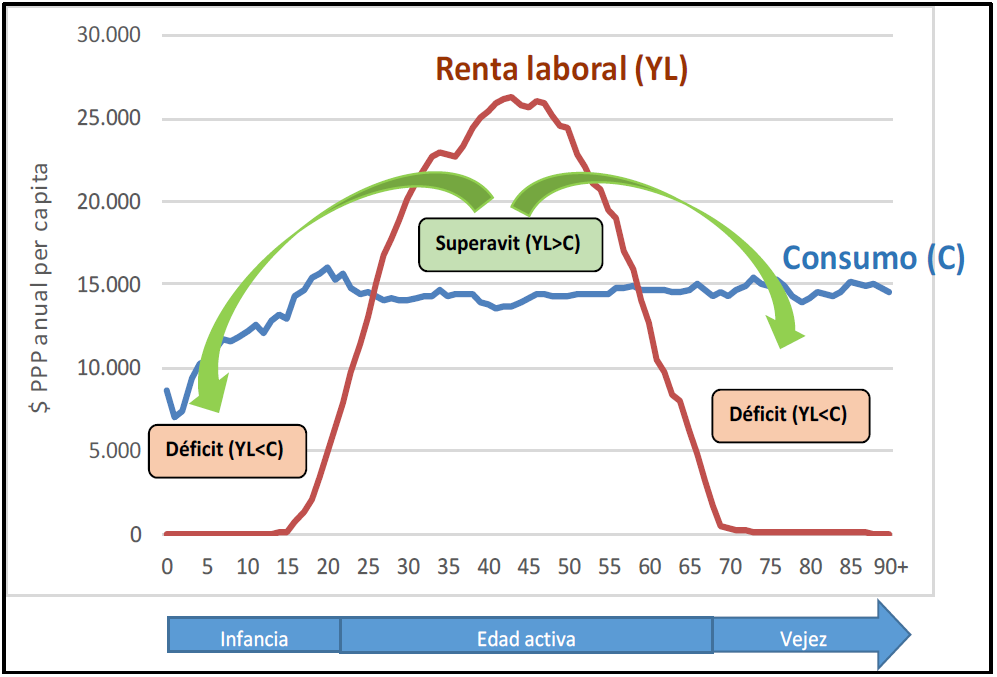

If we are to meet the challenge of population ageing successfully, it is necessary to rethink many of the current structures of social organisation. To understand why, it is useful to start by analysing the structure of people's life cycle. From a strictly economic point of view, depending on whether they are able to generate the resources needed to meet their needs at any given time, three stages in a person's life can be distinguished: childhood, active age and old age. During the former and the latter, given the inability to generate incomes with which to finance their consumption needs, some mechanism of redistribution of resources becomes necessary either intertemporally or between generations, what are commonly called intergenerational transfers.

These mechanisms can be of three types. On the one hand, individuals themselves could use the market to redistribute their resources throughout their lives (saving for old age or, hypothetically, borrowing while young). On the other hand, two other institutions can redistribute resources between different generations: the family (through private, mainly family transfers) and the public sector (pensions for the elderly and education for children). Although in traditional societies the most important mechanism was that of family transfers, throughout the twentieth century most countries developed and consolidated the so-called Welfare State, in which the public sector now plays an important role in the redistribution of resources.

Schematic representation of people's life cycle from an economic point of view. While consumption throughout a person's life is always positive, the capacity to generate income from work is limited to the active age, which means that there are necessarily two stages of life cycle deficit (at the beginning and at the end), while the active age would be characterized by a surplus. Therefore, there must be mechanisms that allow for the redistribution of resources, either intertemporally (from each individual to himself at different stages) or intergenerationally (from assets to children and the elderly).

The Welfare State as a system of intergenerational transfers

The Welfare State is the set of public policies aimed at redistributing income among citizens and ensuring a minimum standard of living for all. These include, in budgetary terms, pension systems, health care and education. There is a variety of other social expenditure programmes, although their quantitative importance is generally much smaller (long-term care, unemployment benefits, housing assistance, etc.). It is not difficult to see that the three major policies mentioned are clearly dependent on the age composition of the population (pensions and health care are primarily aimed at older people, while education is aimed at younger people). However, the income from social contributions or general taxes comes mostly (except for consumption taxes) from the working-age population. Taken together, these programmes basically constitute a solidarity-based system of transfers between the different generations living together at any given time, strongly conditioned by the relative size of each age group.

At the beginning of 2000, an ambitious international project aimed at building National Transfer Accounts (NTAs) was launched in the USA. The aim is to prepare, for each country and each year, a breakdown by age of the National Accounts. In this way, invaluable information is available on how resource flows occur between different age groups in each period, estimating also the resource movements between age groups within the families themselves. Currently, ATNs are available for at least one year for each of the more than 50 countries participating in this project.

The need to rethink the Welfare State: looking to the past to face the future

The first precedents for welfare policies date from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, although the development of the Welfare State itself took place after the Second World War (a little later in Southern European countries such as Spain and Portugal). Obviously, the social, economic and demographic conditions were very different from the current ones. Between 1909 and 2009, life expectancy at birth in Spain increased by no less than 40 years, of which almost 20 years have been earned since 1950. It is not surprising, then, that experts begin to speak of the need to redefine the concept of old age. The delay in the age of incorporation into the labour market, thanks to the improvement in education, is no less relevant. These are undoubtedly two great advances to be celebrated, although their consequences in the definition of life cycle mentioned above are direct: the two stages of economic dependency (childhood and old age) are visibly lengthened, while the active age is reduced given its later start.

This project deals with the analysis of Welfare State policies and their interaction with the role of family transfers throughout history. The objective is to look to the past, analysing the evolution throughout history that allows us to draw lessons to successfully face the challenges posed by the future. The approach must necessarily be multidisciplinary, and for this reason the team is made up of experts in Demography, Economics, History and Politics. On the other hand, an analysis will be made not only for the Spanish case, but also for Portugal and the USA, in collaboration with researchers from both countries.