Diálogo Abierto

How should we measure population ageing: using the old-age dependency ratio or is there an alternative?

Jeroen Spijker

The ageing of the population constitutes a change in the age structure of the population within which older people form an increasing proportion of the total. But while society understands the concept of population ageing, how we should measure it is another matter. In a context of improved survival levels among older people and an underutilized labour market, it could be questioned whether it is advisable to base decision-making on employment and health policies on indicators of population dependency in old age where age 65 is considered the "old age threshold" and age 15-64 the "productive population". For this debate, I will briefly offer the main theoretical arguments and empirical findings to use alternative indicators that measure dependency in old age and provide a reflection for the Spanish case. To conclude, I recommend basing the "old-age threshold" on remaining life expectancy rather than on an exact age to give a more accurate view of the degree of ageing by taking into account improvements in life expectancy at older ages.

Population ageing is the process where low fertility and declining mortality lead to changes in the age structure of the population within which the elderly constitute an increasing proportion of the total. This process is considered to be of economic importance because of a fundamental characteristic of the economic life cycle, namely that adults of working age produce more - through their labour force - than the elderly and the children they support directly or indirectly. But while society understands the concept of population ageing, how we should measure it is another matter.

Society understands the concept of population ageing, but how we should measure it is another matter

So far, probably the most widely used indicator of population ageing is the old-age dependency ratio (OADR), which is obtained by dividing the elderly population (65+) by the working-age population (16-64 or 20-64). An important reason for basing ageing measures on static age limits is the age of eligibility set by public policy in age-related social agreements, in particular public pension schemes. The question that can be asked, however, is how useful such a definition really is because it assumes that there will be no progress on important factors such as life expectancy. Based on previous work (Sanderson and Scherbov 2010, Spijker and MacInnes 2013, Spijker 2015, Spijker and Schneider 2020), the idea of this article is to summarise the main theoretical arguments and empirical findings for using alternative indicators to measure old-age dependency.

From a demographic point of view, one can argue that demographic ageing is "the increase in the average age of a population", as Dr. Julio Pérez claims in his answer to the discussion question. He is right: if the average age increases, the population ages.

For people in general and politics in particular, the average age is of little use. Moreover, and key to the debate, the mistake is made of seeing age as a static concept

This seems obvious. In 1970 that age was only 33 years, in 2000 40 years and in 2019 44 years. The Spanish population has aged 11 years in half a century, but for me this debate is not over! That's because for people in general and politics in particular the average age is of little use. Furthermore, and key to the debate, is that the mistake is made of seeing age as a static concept.

Counting 'dependent' older people

For people aged 65, traditionally the threshold linked to legal pension age and the onset of old age, remaining life expectancy (RLE) has been rising steadily. This leads us to the big question: when is a person considered to be "old" or "elderly"? Existing policies often take the criterion of legal retirement age into account.

The legal retirement age, until very recently, was the same age as when the first public pension system came into force in Spain in 1919, despite the fact that the average probability of surviving from birth to age 65 increased from 32% then to 90% now

However, it is, until very recently, the same age as when the first public pension system came into force in Spain in 1919, despite the fact that the average probability of surviving from birth to 65 years of age has increased from 32% then to 90% now (women a little more, men a little less) and life expectancy at 65 from 10 to 21 years. In other words, can we compare a 65-year-old person today with one a century ago if they have twice as many years to live, or even with one just a decade ago, as there is still no sign of improvements slowing down? I would say not. Perhaps even more importantly, these improvements have not been accompanied by proportionally more years of poor health or physical limitations. In fact, most acute medical care expenditures occur in the last months of life, with little impact of age, while severe disability is being deferred to later ages. To capture the changing meaning of age is to consider that the age of a population consists of two components: the years lived by its members (their ages) and the number of years left until death. In a period where the life span is lengthening, not only does the average age of the population increase, but also the RLE associated with each age. In the context of the elderly becoming "young" the idea of "years remaining" instead of "years lived" can be applied to estimate the proportion of the population that we consider to be elderly.

Instead of making the age threshold of the "elderly" dependent on a fixed age limit, 65, we can make it dependent on a fixed remaining life expectancy

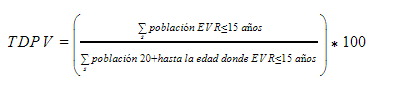

In particular, instead of making the age threshold of "old" dependent on a fixed age limit, 65 years, we can make it dependent on a fixed remaining life expectancy. It is usually used 15 years in countries with low levels of mortality, which today corresponds to about 70 years for men, but equaled about 65 at the end of 1980. An alternative to the proportion of the population over 65 would then become the proportion of the population in age groups that have a RLE of less than or equal to this threshold. Similarly, as an alternative to the OADR, the population with an RLE15 or less can be divided by the population with an RLE over 15 and over 20 (instead of 16 as many teenagers are still in education). This has been called the prospective old-age dependency ratio (POADR):

Counting the 'active' population

However, both the POADR and the OADR assume that everyone of working age also works, although the knowledge economy keeps young people in education longer while many workers aged 60-64 choose or are forced into early retirement (in 2019 only 41% were working). At the same time, more gender equality and dual-career families have added millions of women to the labour market over the past 50 years.

There are more working-age dependents than non-working older people

Using age to define the working population then does not make much sense either. In fact, if we were to count the non-employed, for whatever reason, as dependents we find that there are more dependents of working age than non-working older people. Therefore, a suggested alternative is to apply the same numerator as before, but divide it by the population in paid employment, regardless of age (the Real Elderly Dependency Rate⸺REDR; Spijker and MacInnes, 2013).

An illustration

For the denominator, there are also other variants that take into account economic productivity or tax revenues that reflect the potential capacity of the economy as a whole to be able to cover health and well-being for each dependent older adult (Spijker 2015), but for the sake of argument, only a comparison is shown between OADR, POADR and REDR. The level and trend of these new indicators are very different from the OADR. In the case of the POADR, the dependency ratio is almost the same today (17.3/100 in 2019) as it was in 1950 (17.9/100) and 1970 (16.4/100). By comparison, the OADR was 30.2/100 in 2019, almost twice as high as in 1970 (15.7/100) and almost three times as high as in 1950 (11.1/100). If, in addition to controlling for improvements in the RLE (i.e. considering as an old age threshold the age where the RVT is equal to 15 years) we also include changes in labour participation (since it is the workers who finally pay for the health and pension system) we see that until recently real dependency (RVT) was above the RLE, but due to the increase in the RVT among the elderly and the massive entry of women into the labour market, the ratio fell from the 1980s until the beginning of the previous economic crisis (2008-14). Now, if the employment rate were to rise from 64 per cent in 2019 to 67 per cent in 2030 (which was the level in 2007, the year when the employment rate was the highest in half a century), the REDR would not change at all until 2030.

Figure. The Ageing Dependency Rate (OADR), the Prospective Ageing Dependency Rate (POADR), the Real Elderly Dependency Rate (REDR) and the RADR adjusted for an increase in the retirement age, Spain 1950-2050

(2).png)

Source: The OADR and the population by single age and sex are available from 1950 to 2018 in the Human Mortality Database (www.mortality.org) and for projections up to 2050 on the website of the National Statistics Institute (INE) (www.ine.es). The employment data required for the denominator of the REDR come from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) (www.ine.es). Prepared by the authors.

Discussion

Historically, old age was more related to looking physically old and not being able to care for oneself, but during the second half of the last century age 65 was often used to separate older people from other adults, perhaps facilitated by the coincidence with the age of retirement. However, this is an arbitrary age with little economic, political or individual relevance or validity. The crux of the matter is whether we can compare people of the same age over time if they are now living, 2, 5 or 10 years longer, or whether we can use a denominator that does not reflect the population employed in the labour market.

The OADR defines all people above the legal retirement age as 'dependent', regardless of their economic, social or medical circumstances. However, as the remaining life expectancy (RLE) rises, older people thus become younger and healthier than their peers in previous cohorts. When life span is extended, any age becomes a marker where it is reached earlier in a lifetime and, as a consequence, makes chronological age a poor measure of progress. However, as I have argued previously in a paper where I collected 20 indicators that were in some way related to population ageing (Spijker 2015), the indicator to be used should depend on the aspects of ageing that are being studied. Defining the old age threshold using the age of 65 may be useful for estimating the pension "burden" (although more accurate would be to use the average age of exit from the labour market as it fell from 68 in 1960 to 60 in 2001, although it has increased by 2 years since then) but not for estimating the public health "burden" if the life expectancy (and also health) of older people has risen substantially over the last 5 decades.

In summary, in a context of improved survival levels among older people and an underutilized labour market, economists and public policy makers must be careful to base their arguments and decision making on indicators of population dependency in old age that use age 65 as the "old age threshold" and age 15-64 as the "productive population". Instead, it would be advisable to base the "old-age threshold" on the remaining life expectancy (RLE), as it gives a more accurate picture of the degree of ageing by taking into account improvements in life expectancy at older ages. In contrast, the traditional rate (OADR) forecasts an overestimated level of ageing, but which neo-liberal economists and politicians have used for their alarmist speeches, seeing it as a threat to economic growth and government budgets. In fact, an ageing population even has the potential for economic growth with the right policies in place.

In conclusion, it is important that politicians realize that the same age is not always comparable over time. New retirees know that they will spend more inactive years than previous generations (Post and Hanewald 2012), which is, in time, an incentive for people to accumulate assets for retirement and continue to work beyond age 65. In this sense, the POADR measurement represents a "higher level" of optimism about the potential release of human capital by optimising the experiences of the population over 65 who still have an RLE over 15. It could be said that this group of our society is often, but erroneously, described as "old" or "dependent" given their good health, their non-economic participation in society and their economic independence (Spijker and Schneider 2020).

Looking at old age from its two dimensions, chronological age and remaining life expectancy, rather than just one, gives us a more balanced picture of ageing

Although the modification of the structure of the population due to the increase in the RLE is a dimension which has not received sufficient attention due to the fact that it is technically more complex to measure (Spijker and MacInnes 2013), incorporating this new dimension for the analysis of ageing would help to complement the traditional image of chronological age on which this dynamic is analysed. Looking at old age from its two dimensions rather than just one offers a more balanced picture of ageing.

References

Post, T. & Hanewald, K. 2012. Longevity risk, subjective survival expectations, and individual saving behavior. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 86(200-220.

Sanderson, W. C. & Scherbov, S. 2010. Remeasuring Aging. Science, 329(5997), 1287-1288.

Spijker, J. 2015. Alternative indicators of population ageing: An inventory. Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers 4/2015. Vienna Institute of Demography. Available: www.oeaw.ac.at/fileadmin/subsites/Institute/VID/PDF/Publications/Working....

Spijker, J. & MacInnes, J. 2013. Population ageing: the timebomb that isn’t? British Medical Journal, 347(f6598).

Spijker, J. & Schneider, A. 2020. The myth of old age: Addressing the issue of dependency and contribution in old age using empirical examples from the UK. Sociological Research Online, Online first. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780420937737.

Julio Pérez

Jeroen Spijker is not only one of today's real experts on this subject, but we are friends and work together for many years. That is why I will interpret his question as an invitation to express my criticism, which he knows well, not only of the concept of "ageing population" itself, but also of the debate on how to measure it.

"Demographic ageing" is a metaphor, typical of the prevailing organicism in the origins of the discipline of demography. And as I have repeatedly explained (https://apuntesdedemografia.com/envejecimiento-demografico/que-es/447-2/), it is a fallacious and malicious metaphor, coined by the fierce natalism of the first decades of the 20th century. It denotes a lack of understanding of the causes and mechanisms of the reproductive revolution that has brought us to the current demographic system, but also a remarkable effort to tinge it with negativity and to fight against it. Today, we know that low fertility is much more efficient, but providing long lives to all those who are born. In fact, this is the strategy that, in little more than a century, has multiplied the human population to unprecedented numbers.

I insist; populations are not organisms that are born, develop to maturity, and then age and die; populations have no age, they do not age, as the catastrophists who are bent on treating falling fertility as a symptom of decline and extinction claim.

The process we call "demographic ageing" is in fact the change in the age composition, that which is graphically depicted by the population pyramids. It is not true that it only results from lower fertility and longer life expectancy. Migrations also produce it, when many younger people migrate or when many older people migrate (in fact, rural ageing is explained in this way, not by reproductive changes). Only if we focus on planetary, systemic ageing, that of the whole of humanity, does it in fact result from the new reproductive dynamics, based on longer lives and fewer children per woman.

In any case, it is a process that demographers know how to measure without ambiguity or equivocation, in a very simple and understandable way, with an indicator that is not affected by the historical moment or the particular population to which it applies. Jeroen's question (How should we measure population ageing: using the old-age dependency ratio or is there an alternative?) is based on a false problem and an accumulation of misunderstandings and traps set by current language. The level of demographic ageing is measured by calculating something as simple as the average age of all the components of the population we are interested in. So much so that it could be defined in this way: demographic ageing is the increase in the average age of a population.

All the doubts begin when the proportion of older people in relation to the whole population is used, a simpler and easier indicator to calculate, but one that brings us back to the misunderstandings. If demographic ageing is identified with the increase in the proportion of older people, a methodological and analytical problem is created which is not related to demography, and through this gap, an anthropological, sociological and even philosophical question arises which is difficult to exaggerate, but which is very different, which is the age at which we establish the cut between older people and non-elderly people. In other words, when does old age begin?

This is the real question behind Jeroen's question, because we are all capable of seeing that old age is not reached at the same age under the present conditions as it was only a few decades ago. If we maintain a limit such as 60 or 65 years, the passage of time makes it obsolete and asks us to review the criteria with which it was established at the time.

If we choose to construct an indicator that establishes a mobile limit to define what we consider to be old age at any given time, each person can propose their own (sociologists, biologists, anthropologists, doctors...)

There is room for very important lines of research on the social and symbolic significance of each age, on the historical change in health and disability, on the beginning and end of working life, on the generational differences in living conditions during the life cycle, and even on the values with which each human group attends to and treats those who are at different stages of life. And in all of them the collaboration of demographics can be useful. But interdisciplinarity cannot lead to the abandonment of the concepts, methods and specificities of each discipline, and demography would be wrong to forget that its specific field of research is much clearer and more systematic than that of most other social sciences and that, above all, this specific field is not in any of these lines. With an addition of some importance: if we choose to construct an indicator that establishes a moving limit to define what we consider to be old age at any given time, each person can propose their own (sociologists, biologists, anthropologists, doctors...), thus increasing the current difficulty and, furthermore, it becomes equally difficult to compare historical moments and different places, as each one would be obliged to determine their own limit beforehand.

I am sorry to disappoint anyone who expected a different approach, but I am a demographer and I understand that I was asked the question as a demographer. As such, I must say emphatically that the doubt about the best way to measure the degree of demographic ageing is false, while the other doubt, the real one, about the best way to set the barrier between adult life and old age does not seem to me to be very relevant, by the way, to demography. Probably one of the consequences of demographic change has been to blow up that barrier.

I do not know if this is possible, but if it is, I would like it to be noted that the author maintains his own website on demographics in which demographic ageing plays a central role: https://apuntesdedemografia.com

Similarly, if possible, refer to any publications of your own on the subject of the question,

Abellán García, A.; Pérez Díaz, J. (2020) Cuatro décadas de envejecimiento demográfico, en J.J. González -Ed-, Cambio social en la España del siglo XXI. Alianza Editorial.

Pérez Díaz, J. (2018). Miedos y falacias en torno al envejecimiento demográfico, en A. Domingo -Ed- Demografia y Posverdad. Estereotipos, distorsiones y falsedades sobre la evolución de la población. Barcelona: Icaria.

Amand Blanes

The advances in the longevity and health of individuals, which constitute one of the main achievements of contemporary societies, make it necessary to rethink the indicators used to quantify the so-called demographic ageing, overcoming the classic segmentation based on fixed age criteria. It is obvious that age 65 does not mean the same thing when life expectancies remaining at that age are 15, as in the 1960s, as when they are 21, as at present, or when they reach 24, as is predicted for the middle of this century. Therefore, it is necessary to integrate into the ageing measure criteria that modify the age from which the older population is considered according to the remaining life expectancy at any given time. These indicators can be further refined by introducing health status, since as age moves, situations of dependency and/or limitations to daily life activities become more relevant. The criterion for establishing the age that defines the older population would then be the remaining life expectancy in good health or without dependency. The use of these indicators modulates the growth rate of the elderly population in the coming decades and allows a wider understanding of the phenomenon of population ageing, overcoming the most catastrophic views of demographic development.

In the debate on the sustainability of the Welfare State, indicators based on the mere numerical relationship between ages, such as demographic dependency ratios or rates, are often used and abused. These ratios, in addition to being based on fixed age criteria, do not take into account levels and variations in the population's activity, state income or transfers received at different stages of the life cycle. The construction of dependency indicators that also integrate variables related to employment or productivity makes it possible to shift the focus of attention and debate from the demographic sphere to the economic sphere, especially in countries with relatively low labour participation in young and mature ages and/or among women. Then, at least in the short and medium term, the key would be the capacity of the economy to generate jobs and increase productivity, and of the State to redistribute wealth.

In the debate on the sustainability of the Welfare State, indicators based on the mere numerical relationship between ages are often used and abused

Finally, not only the measure but the concept of old age itself must be reformulated. The characteristics of tomorrow's elderly will not be the same as those of today, even more so in countries like Spain which are characterised, especially for women, by strong differences in the life cycle between the generations born in the first and second half of the 20th century in many areas such as education, forms of cohabitation, labour and social participation, among others. In this sense, the debate on what is known as "demographic ageing" goes beyond mere numbers.

María ángeles tortosa y Gerdt sundström

We would like to thank the author and add some extra comments on the handling of this dependency ratio and which affects the pension system and indirectly the Dependency System:

First, we think that using the dependency ratio in the pension system contributes to the fact that this abstract figure is being used and not a real one to include elements in the design of the system that are damaging the purchasing power of the elderly; and second, that the use of this ratio should not be a disincentive for pensioners to work while they are pensioners. That is, they should not have their pension reduced if they have other work or income.

Using the dependency ratio in the pension system should not be a disincentive for pensioners to work while they are pensioners

In Spain this is the case, while in Sweden they do not have LOWER taxes for working pensioners and lower employer's tariffs for these cases ... The important thing is to make it easier for pensioners to continue working without this reducing their pensions.

In this way, we believe that older people will feel socially productive and useful as a significant part of their work and taxes would contribute to generating public income and wealth at the national level. Professor Spijker suggests raising the official retirement age: this was done recently in Sweden. Currently it is 66, then 67 and then 68, because of increased survival after retirement. But, in addition, people can (and could before) obtain their pension up to four years before the set age (66) and up to a few years later, either by reducing or increasing the pension, as the case may be. In Sweden, older people are increasingly working: in 2001, 9% of the 65-74 were in paid employment, in 2010 13%, and in 2019 18%. The rates were higher among men than women: 13% and 6%, 18% and 8%, and 21 and 15% respectively. One third of them were in full-time employment (Arbetskraftsundersökningarna 2019) / Swedish Statistics' Labour Force Surveys/

In parallel, we would like to point out a confusion similar to that of the dependency rate and which occurs in the analysis of the System for Autonomy and Care for Dependency and in Long-term Care when the "access to carers" ratio is used. This ratio compares those over 65 years of age with people between 45 and 64 years of age ("potential group of middle-aged carers", generally women) The latter group is getting worse and worse. Therefore, we are facing a problem similar to the one suffered by the dependency ratio, since this ratio on carers is also very affected by the demographic changes and changes in the groups of people who can actually care.

Again, in this situation what matters is not these arithmetic calculations and abstract figures, but the real situation of the elderly. As J. Spijker says, it is important to know the number of elderly people in real need, and then the number of carers who can potentially care for them in the end, and these are not all people of caring age.

At least in Sweden and probably also in Spain, older people now have MORE carers available (partners and children) than before. In fact, much of the family care (always bigger than public services) is provided by couples, men and women, both in Spain and in Sweden (Abellán, A; Pérez, J; Pujol, R; Jegermalm, M; Malmberg, B. & Sundström, G. 2017. Partner care, gender equality, and ageing in Spain and Sweden. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 11, 1, 69-89.)

In the past, older people in Sweden had on AVERAGE more middle-aged children (because that generation had more children), BUT also more older people had none: 23% childless among 67+ in 1954; by 2019 it is 10%, and many more live with a partner. If the neighbours have many children, it may not help the person who has none These data can show the differences between the use of real numbers and those coming from arithmetic calculations of the ratio.

According to the current arithmetic calculations of the ratio access to care it follows that only a few older people will have potential carers, while reality shows that more older people have children and partners = potential carers. And that is why we believe that this ratio should also be modified and is not useful because it does not show the real situation of the families.